A detailed look at one of my favourite paintings.

Holland in the seventeenth century was a nation divided by religion. The north was largely a protestant community, whilst the south, still under Spanish rule was predominantly Catholic. Northern Dutch painters were increasingly looking to subject matter that moved away from what they saw as grandiose Catholic ideals of beauty; as such, portraiture, landscapes and still life became the dominant genres of painting in the period. Meanwhile, in the south, the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens carried on revelling in an expansive Baroque pomp that drew inspiration from the colour and figure arrangement of Titian and manifested itself in vast Biblical and allegorical epics.

Rembrandt fits somewhere in the middle of this picture; along with the comprehensive autobiography he has left us in over sixty self portraits, numerous portraits of others and an accomplished oeuvre of engravings; a protestant, he is famous for his incisive treatment of certain, perhaps otherwise neglected passages of the Bible. A good example of this is The Reconciliation of David and Absalom which sacrifices a fashionable idealised notion of beauty in favour of a sincere, naturalistic portrayal of the shame of a son in submission to his father.

It is important to point out, although it might seem obvious, that a self-portrait is not subject to the demands of a patron. There was never a space on a wall allocated for this particular representation of the artist. It would be absurd for a seventeenth century patron to have requested an artist’s self-portrait. These patrons wanted a steady stream of specific historical or biblical scenes, picturesque landscapes or portraits of themselves. This explains the size of this particular picture, which is small, only 53cm by 44cm – size being solely the artists decision. Perhaps Rembrandt painted such a small picture for purely practical reasons, to carry it around and so forth. One suspects huge canvases would not have been appropriate for his personal project; to study and accurately represent his face – rather than idealise it in fashionable grandeur.

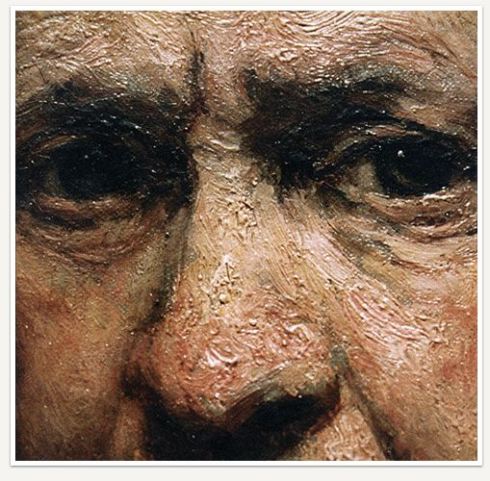

Many of Rembrandt’s self-portraits follow a distinct structure; dark, deep brown backgrounds, understated clothing, any light in the pictures directed on the artist’s face: this produces a dramatic and engaging effect. The Self-portrait Aged 51 thrives on such intimacy.  Rembrandt’s upper half emerges from a cloying brown background, devoid of any sensuous extravagance. Very little space surrounds the dominant head, which forces the spectator to meet the artist’s direct gaze. The eyes are a moment of clarity in the artist’s rough, bearded face furrowed with lines. The areas immediately surrounding the eyes and the artist’s forehead are particularly textural and expressive. Rembrandt’s use of an impasto technique on these areas draws our attention to the surface of the canvas and amplifies the contrast between the artist’s face and the smooth, deep background. Equally important is the focus of light in the painting, which comes from an unknown, unseen source and is directed at the eyes and forehead. These aesthetic decisions serve to draw the spectators eye in to closely studying the facial expression.

Rembrandt’s upper half emerges from a cloying brown background, devoid of any sensuous extravagance. Very little space surrounds the dominant head, which forces the spectator to meet the artist’s direct gaze. The eyes are a moment of clarity in the artist’s rough, bearded face furrowed with lines. The areas immediately surrounding the eyes and the artist’s forehead are particularly textural and expressive. Rembrandt’s use of an impasto technique on these areas draws our attention to the surface of the canvas and amplifies the contrast between the artist’s face and the smooth, deep background. Equally important is the focus of light in the painting, which comes from an unknown, unseen source and is directed at the eyes and forehead. These aesthetic decisions serve to draw the spectators eye in to closely studying the facial expression.

In stark contrast to the expressiveness of the artist’s skin, and it’s manifestion in Rembrandt’s course brushwork is the black hat on his head, which, in terms of paint is smooth on the canvas and utilises the visual silkiness of velvet. The Dutch biographer Arnold Houbraken believed that Rembrandt didn’t want his pictures examined closely because when seen up close his ‘bad’ technique would be evident. He remarked that Rembrandt kept people away by telling them that ‘the smell of colour will bother you.’ Rembrandt’s ‘bad’ technique, as he puts it, refers to the way he describes things with paint rather than by careful line drawing. In Self -portrait Aged 51 there seems to be a synthesis of these two representational styles; while the face emerges in and from the movement of paint, the delicate hat seems a result of measured drawing. This kind of duality illustrates the difficulty of placing Rembrandt within a particular school of painting; he appropriates both the painterly aspects of, say, Titian and the delicacy of Raphael.

Through a series of contrasts then, Rembrandt invites the spectator to study the visual minutiae of his face. Vitally however, the closer and the deeper one looks, something becomes inverted; no longer does one simply look at the visual minutiae of the artist’s face, one begins to see the innumerable decisions Rembrandt has made, the dabbing, twisting and dragging of paint, the fundamental abstraction of the painted mark.

Taking a step back for a moment, Rembrandt’s direct gaze then becomes particularly significant; it is the gaze of an artist closely studying and creating a subject. Perhaps, the moment we begin to closely study this painting and engage with his gaze we actively participate in much the same process. Rembrandt captures the moment of complicity between a picture and it’s spectator.

Taking a step back for a moment, Rembrandt’s direct gaze then becomes particularly significant; it is the gaze of an artist closely studying and creating a subject. Perhaps, the moment we begin to closely study this painting and engage with his gaze we actively participate in much the same process. Rembrandt captures the moment of complicity between a picture and it’s spectator.  As we look into his eyes we realise that this moment is a profoundly human experience. We glimpse a moment of character in this self portrait, something precious and fragile which illuminates and is illuminated by Rembrandt’s perpetual gaze.

As we look into his eyes we realise that this moment is a profoundly human experience. We glimpse a moment of character in this self portrait, something precious and fragile which illuminates and is illuminated by Rembrandt’s perpetual gaze.

Rembrandt’s painting style is often associated with a deep, genuine knowledge of that which is human in his subjects, rather than that which is affected or desired by the sitter. E.H Gombrich states in relation to Rembrandt’s portraiture that while ‘other portraits by great artists… are memorable for the way that they sum up a person’s character and role … Rembrandt must have been able to look straight into the human heart.’ He seems to have been able to subject his own image to an equally, if not more thorough character analysis than his portraits of others. Gombrich states that ‘Rembrandt certainly never tried to conceal his ugliness,’ and indeed we are left little to the imagination, his face has it’s imperfections and there seems to be no contrived attempt to conceal them. Equally Rembrandt does not try to conceal his mood. Although the pose is dignified enough, the tone of Self-portrait Aged 51 is distinctly melancholic. There is something remarkably lonely in Rembrandt’s tiny representation of himself.

There are several angles from which one might approach these ideas. From a modern perspective, we might be inclined to suggest that Rembrandt is engaged in an attempt to romanticise the solitary figure of the artist; intensely, even obsessively pursuing representative perfection whilst simultaneously alienating himself from society. This might be one way of looking at Rembrandt, as a forerunner of Romantic constructions of what the artist stands for; however, we might also, I suggest come to a more vital understanding of the tone of this self-portrait if we look at it in terms of the artists personal situation. In the years preceding the painting of this self-portrait Rembrandt’s wife and child died and between 1656 and 1657 Rembrandt went bankrupt. Yet it would be dangerous and trivial to assume that these events provided the direct impetus for Rembrandt to paint a portrait of himself looking melancholic.

It seems absurd however to suggest that he would expurgate the sadness in his demeanour, engendered by the traumatic events in his life, if he aimed to produce a picture that reflected the aesthetic truth of his character. The moment captured seems to betray a pervasive mood of sadness; and this sadness operates through directness of form and technique, it might then seem reasonable to allow a biographical note of interest to colour our interpretation on this particular point. An analysis of an artist’s life and an analysis of his paintings are separate things. In the case of Rembrandt his self portraits tempt us into a reconstruction of his life and work; the enigma of his gaze launches us back into the past in search of an answer. Gombrich’s sentiments reflect this kind of opinion, he reminds us that;

‘Rembrandt did not write down his observations as Leonardo and Durer did; he was no admired genius as Michelangelo was, whose sayings were handed down to posterity; he was no diplomatic letter writer like Rubens, who exchanged ideas with the leading scholars of his age. Yet we feel we know Rembrandt … more intimately … because he left us an amazing record of his life in a series of self portraits ranging from the time of his youth when he was a successful and even fashionable master, to his lonely old age when his face reflected the tragedy of bankruptcy and the unbroken will of a truly great man.’

The way we interpret Rembrandt and his representation of himself in Self Portrait Aged 51 seems to rely not merely on an analysis of the formal elements in the painting and whatever insights we might bring to the painting about Rembrandt’s financial and spiritual condition; we should equally take into account what it means to be a spectator looking at a self-portrait, inhabiting the position of the artist, a concentrated observer of form and physicality. This picture has a marked psychological aspect, hinted at by the focus of light on the artist’s forehead. Rembrandt articulates a type of artistic complicity that is peculiar to self-portraits, particularly his own attempts at self-portraits; the more we gaze at the artist, the more mysterious he becomes and the more we illuminate something in ourselves. Perhaps this is Rembrandt’s greatest gift. But can we really agree with Gombrich in saying that we know the artist ‘more intimately’ because of this. How well do we really know him? One might ask the question whilst peering into Rembrandt’s eyes, where does Rembrandt – the artist – end and the onlooker begin?

Bomford, David. Art in the Making; Rembrandt. London: National Gallery Publications, 1988.

Clarke, Martin. A Companion Guide to the National Gallery of Scotland. Belgium: Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland, 2000.

Gombrich, Ernst. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon Press, 1995.

Von Sonnenbrg, Hubert. Rembrandt / Not Rembrandt; Aspects of Connoisseurship. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications, 1995.

White, Christopher. Rembrandt. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984.

University is difficult isn’t it. Essay writing dragging you down? I offer private tutoring services for Bachelor’s Degrees in English Literature and Art History 1st to Final year level; will also help with Philosophy, History, Creative Writing 1st to 2nd Year Level; News & Magazine writing for Journalism Students; will also tutor at Higher & A-level English, HND, HNC etc.

Have bagged A’s at GCSE, Higher & A-level English. MA from Edinburgh University 2:1 (dissertation 80%) in English Literature. Also Masters Degree in Journalism from Edinburgh Napier University. Prices are reasonable. £20-25 per hour. All students I have worked with have benefited from better results. Edinburgh area only please. Limited places as I only do a few hours of tutoring per week. Contact: alasdair.peoples@gmail.com for more info